Space Shuttle Launch Complex 39-B Construction Photos

Page 60

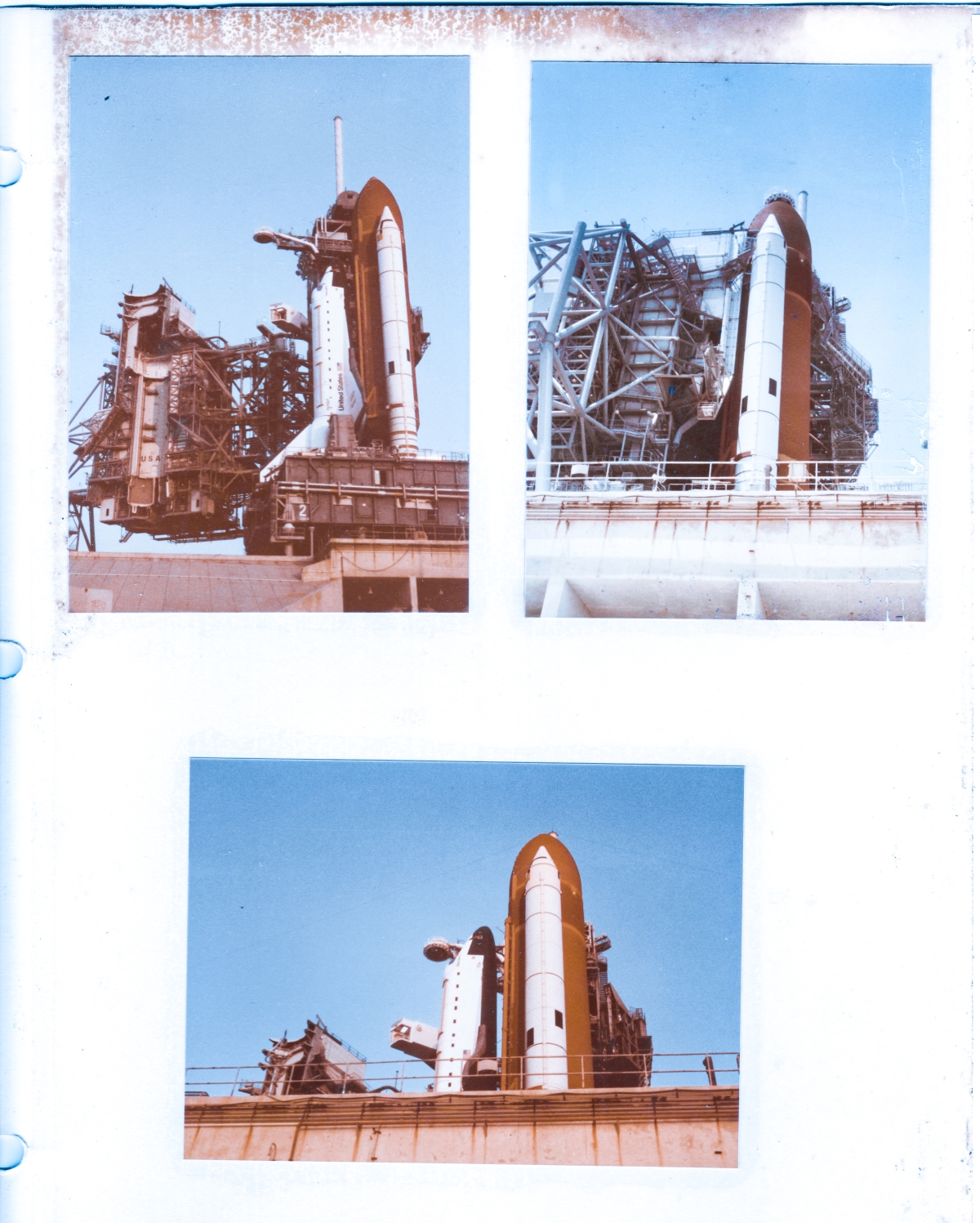

Discovery: Initial Rollout To Pad A (Original Scan)

Top left, and bottom: We drove over there early in the morning from B Pad, and went around on the perimeter road to the east side, and then took the interior pad road toward the High-Pressure Gas Storage Area, and I was blazing away with my camera as we did so. Completely non-official. Interestingly, you can see the Orbiter Access Arm midway between being mated with the shuttle, and retracted back into the latchback position against the tower. We found out later that they had ever-so-slightly mispositioned the MLP on its support pedestals initially, and had to lift it up, put the crawler into reverse and back away from the pedestals far enough to allow for a slight turn/realignment, and then go back forward to reposition it correctly and set it back down. We had, by complete random luck, arrived just as they were operationally backing out from the initial misaligned setting of the MLP, and the OAA was in the process of being retracted prior to jacking things back up and then picking up the stack and putting the crawler into "reverse" when these shots were taken.

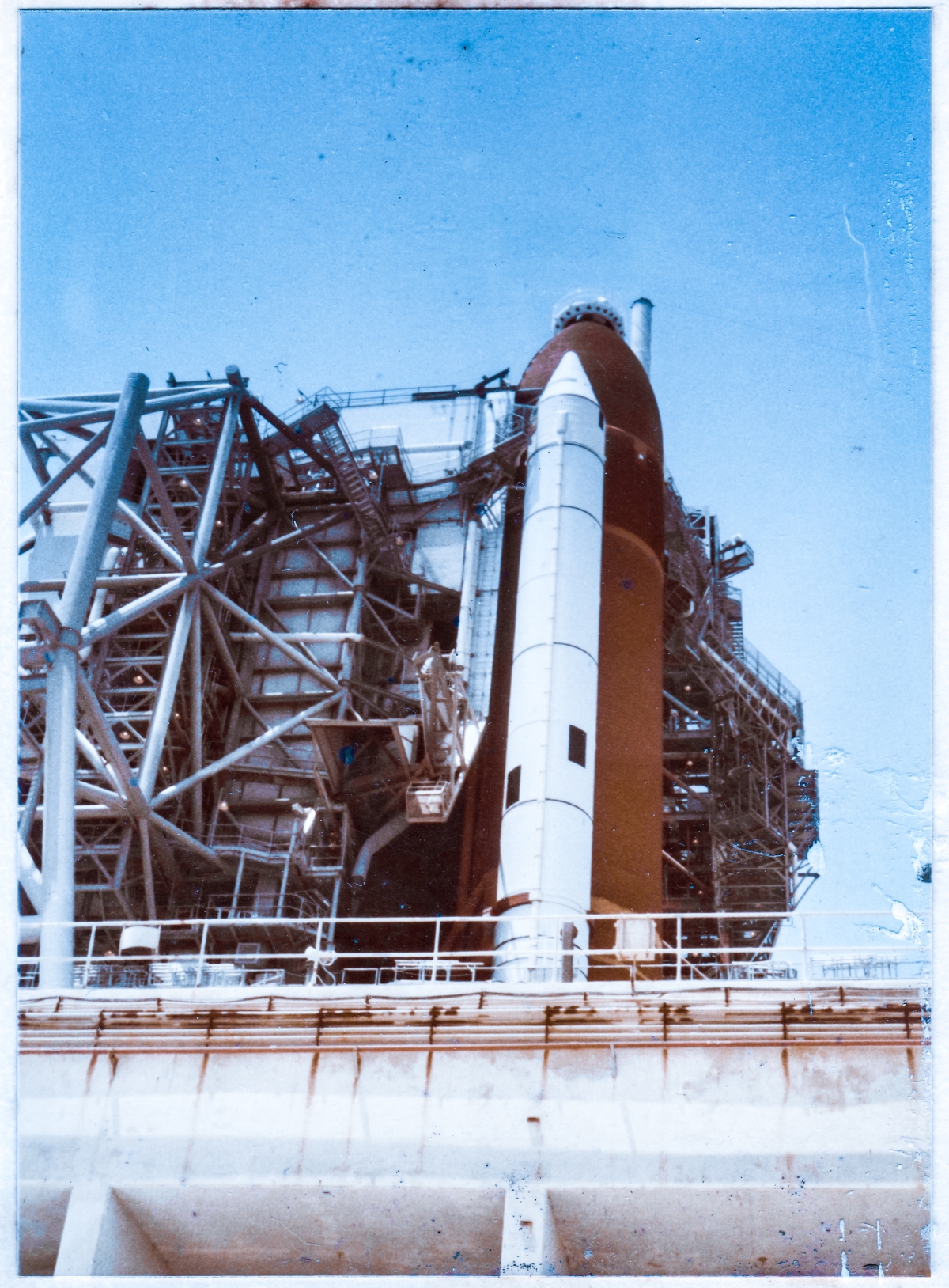

Top right: Later that day, when all was well and the RSS was mated to the Orbiter.

Top Left: (Reduced)

Jack Petty and I had arrived at work early, as always, before the 7:00am start of work for the craft labor, and this just happened to be underway on a gloriously-clear Florida Morning, August 10, 1984, and by 7:30am we found ourselves looking out the windows of Jack's BRPH company car, staring in amazement at the sight you see here, from an unusual vantage point near the end of the access road which leads to the High-Pressure Gas Storage Area on the east side of the pad.

The two of us shared an interest in the overall program, above and beyond the narrow confines of our own jobs, and if an opportunity presented itself, we would seize it, and on this particular morning, we seized what turned out to be a very good opportunity indeed.

We were a familiar sight to all of the security operatives on A Pad, and also had at least the minimal good sense to not drive right up on top of the pad, directly underneath the thing, and instead took a path less followed, around to the right, past the Oxidizer Hypergol Storage Area, and then left on the access road that takes you into the High-Pressure Gas Storage Area which consists in a large well-buttressed cutout into the east side of the pad slope.

We knew what we were doing was unauthorized, but like a couple of little kids, we could not resist, and we just had to do it.

There was nobody around anywhere at all on that access road, nor were there any people or vehicles near the gas bottles in the cutout.

Dew-on-the-grass early-morning, sun slanting near-sideways in from the east, just above the horizon. Cloudless sky. Better lighting could not have been dialed up on a machine, if such a thing had existed.

And the timing. Oh god, the goddamned lucky-dog timing of it all. The sheer stupid dumb luck.

I work hard to cultivate my good luck, and yes, such a thing really is possible, but they do not say "Fortune favors the prepared mind," for no reason, and on this day, with no advance warning of any kind, with no prior expectations whatsoever, our minds were nonetheless prepared.

And the luck consisted in the fact that they'd parked the MLP in the wrong place when they first rolled out in the pre-dawn darkness, discovered their error, and then had to back the damn thing off its pedestals, realign it some, and then return to the pedestals and set it back down again where it belonged.

And none of this is in any way trivial, easy to do, or quick.

They're handing a multi-million pound National Asset, possessed of literal kiloton explosive-yield energy, and you can bet your ass they're gonna be damn sure things are gonna be where they're supposed to be, things are gonna be what they're supposed to be, and things are gonna be when they're supposed to be, and if it takes a full hour and a half just to put the goddamned crawler into reverse, then by god they're going to take that full hour and a half just to put the crawler into reverse, and it was this aspect of things that gave me and Jack the opportunity we wound up seizing that bright Florida morning.

Had things gone exactly to plan on their first set-down onto the MLP Mount Pedestals, the entire operation would have been long over and done with before we had so much as shown our badges at the guard shacks, on our way driving separately in to work from opposite ends of the Cape with our headlights still on.

But things did not go that way.

And apparently, they weren't really, fully, satisfied they needed to back away and repark the damn thing until after they'd swung the OAA around into the extend position where it would be butt-up against the crew hatch on the side of Discovery, which meant that as part of the backing-away operations, they had to retract the Orbiter Arm, to get it out of the way first, and mirable dictu, there we were, creeping up on them down by the High-Pressure Gas Storage Area, camera at the ready, while they were in mid-retract, and that's why you see the Orbiter Arm where you do in this image, neither here nor there, but instead, hanging out into empty space to the left of the orbiter, complete with wide-open end, and the lights still turned on in the clean room, which, even more miraculously, the goddamned stupid dumb-luck early morning light was still low enough to allow the lights in the clean room at the end of the OAA to actually show, as opposed to being completely washed out by the overwhelmingly-strong light of normal daylight.

No, I don't believe it either, and yet here we are, staring directly at it.

So ok. So I guess we have no choice in the matter, do we?

Nope. No choice at all.

It was real, and it happened, and goddamned if I didn't manage to get a picture of it.

We did not stop and actually get out of the car, but instead, we crept ever so slowly, windows down, necks craned, closer and closer, me with my camera, half hanging out of the car, clicking away as we crept.

The Space Shuttle, and the towers behind it, loomed impossibly into the sky over our heads, growing ever-larger as we crept closer and closer.

Of note, please be advised that this is not an enlargement of the image in the top-left of the scan up at the top of this page. This is an enlargement of an 8x10 print of that image which I had made at the time, and which seems to have better withstood the ravages of time, and which, even though it's taken from the exact same long-lost original negative, it possesses higher quality, and I'm using it instead. Same picture, different, better, print version of it.

Just so you know, ok?

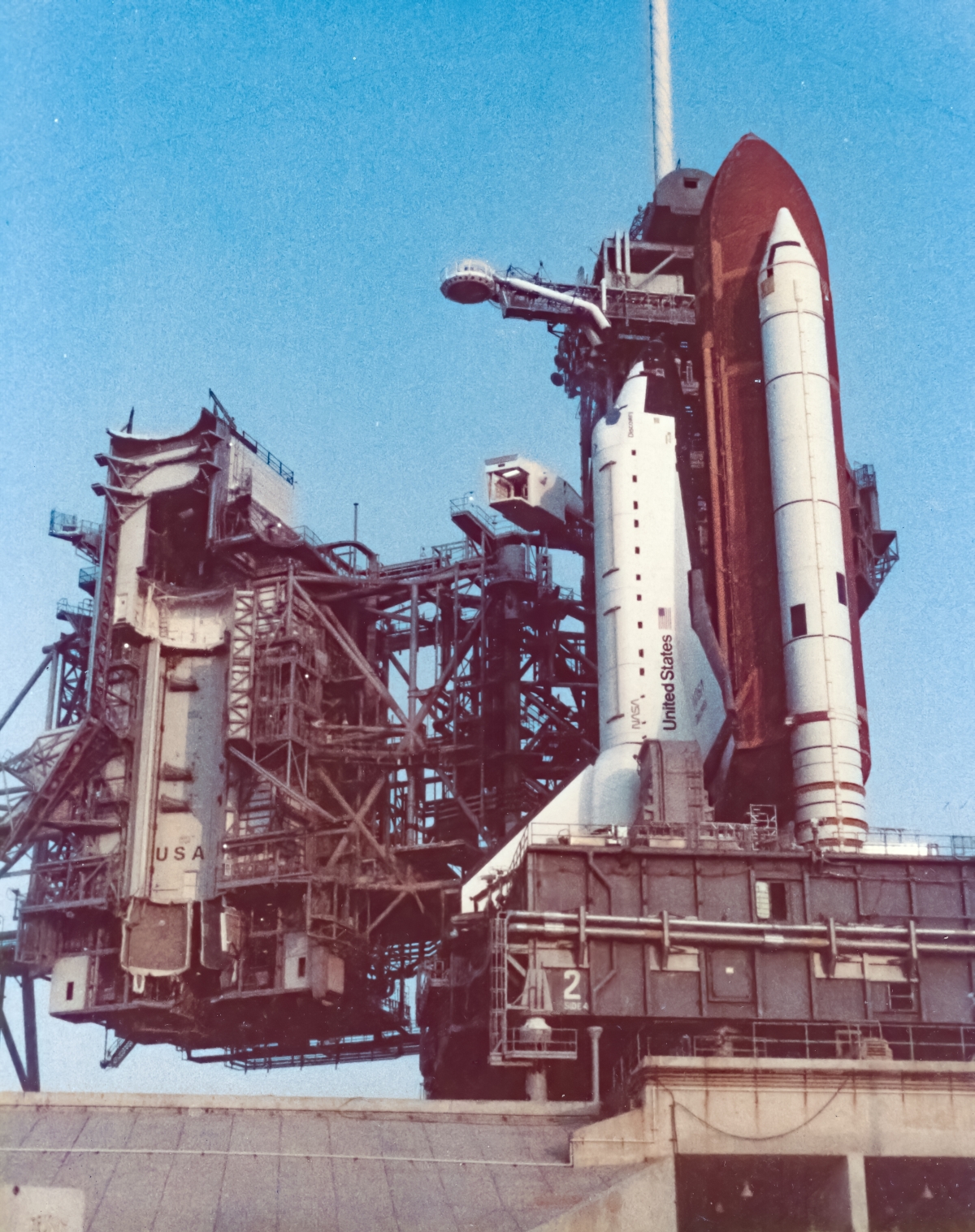

Bottom: (Reduced)

And by this time, we were rapidly approaching the open maw of the High-Pressure Gas Storage Area, and had we gone any farther we would have wound up inside the pad, and inside the pad is probably not the best choice of areas to get a close look at things that are sitting on top of the pad, so we rolled around in a nice slow u-turn, and retraced our path back out toward the Perimeter Road and from there headed back to B Pad where there was more work to do.

In this image we'd come pretty much dead-even with the stack and you can clearly see the blue sky showing through the space between the orbiter's belly and the External Tank from which it's hanging.

Drive any farther toward all those compressed-gas pencil-tanks inside the Storage Area (visible, standing on-end, painted white, in this image, directly below the MLP down at ground-level), and the concrete of the pad deck which by now was already completely obscuring all of the MLP and almost all the the RSS would rise that much higher into the sky and wind up obscuring everything, and what's the point of that? "Yeah, we're nice and close to it now, aren't we?" "Yeah, that we are." "Too bad we can't see it anymore."

One hell of a view in person from right here, though. In some places, more than others, you get better ideas as to the scale of things out here, and from inside Jack's car on this particular morning, looking out the windows, the perspective had gone beyond stunning, and was moving into intimidating territory.

That handrail at the edge of the concrete that's blocking your view of the MLP down below the orbiter is already fifty feet above you, and the size and mass of what's behind it there, reaching skyward, and not by just a small amount, well...

Stuff like this can give you vertigo if you let it. You're looking so far up that your mind starts worrying about things toppling over, and even though your conscious intellect knows no such thing can happen, your brainstem and spinal cord have no faith or trust in any of it, and they're kind of looking around, kind of making sure you can get the hell out of there, in a hurry, if things suddenly decide to come crashing down.

It's different from walking into the streetside entrance of a skyscraper somewhere downtown in a big city. The skyscraper, after a very short time, sort of just fades from view and disappears, and your mind simply dismisses it, and that's the end of that.

Not so, the Space Shuttle. The Space Shuttle had an extraordinarily powerful mana, and the fucking thing would not let go. Would not release you. Held you in its thrall. Demanded you pay heed to it.

And you did, like it or not.

I dunno. It's really hard to explain. Hell, I walked high steel as part of my job duties for god's sake, and still my mind would never quite let go of thoughts like this.

Yeah, the damn thing is intimidating.

There's really no other word for it.

You feel the sonofabitch when you get this close to it, looking up from down below.

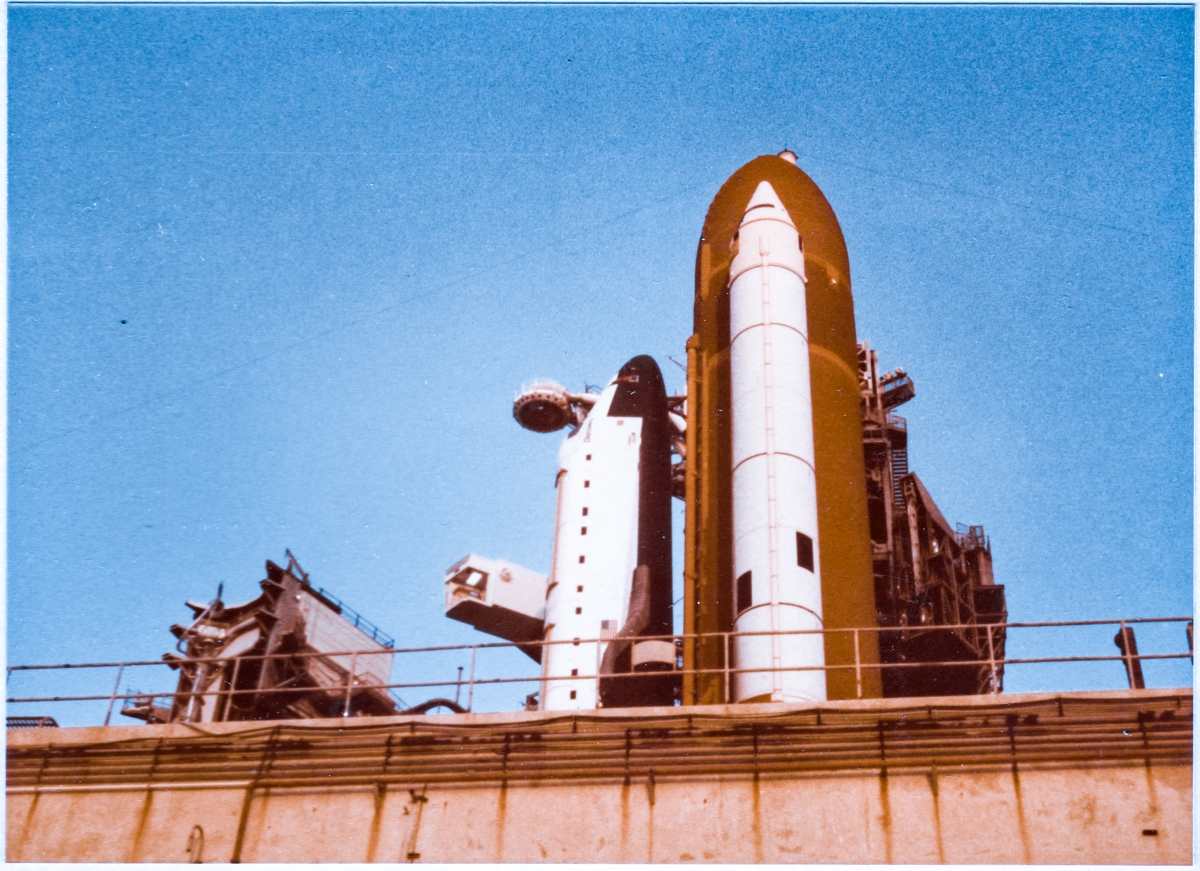

Top Right: (Reduced)

And then later on, during our lunch break, we drove back over to Pad A.

By this time, the RSS had been rotated around into the mate position, completely enveloping and obscuring the orbiter.

To look at this image, taken from just slightly farther away, where you can see a bit more of the bottom of the Right SRB and ET, you'd never know there was an orbiter in there anywhere.

But there is.

And if you look close, just left of the lower portions of the SRB and the dark-orange dimness of the ET beyond it, in the area above and behind the handrail that demarks the perimeter of the pad deck concrete, that blackness you're seeing there is the black TPS Tiles which line the underside of the orbiter's right wing.

And up and to the left a trifle from that black, below the contrapted, cocked-angle steel of the bottom of the right ET Access Guide Column and the OWP encrustations associated with it, extending down and to the left in a bit of a bent curve, out from behind the small rectangular platform and handrail which hangs at the very bottom of the Guide Column framing, you can see what appears to be a whitish "duct" or "pipe" which stops short, abutting the PBK & Contingency Platform on the RSS.

But that is no duct, and neither is it a pipe. That is the reinforced carbon-carbon leading edge of the orbiter's right wing.

Click on this image, click again to fully enlarge it. In the deep gloom just below the end of the reinforced carbon-carbon, a dim vaguely-triangular shape extends farther down all the way to an area which is partially obscured behind the top handrail pipe guarding the perimeter of the pad deck, starting out immediately below a pair of light hairlike flaws in the photograph.

And that "triangle" is in fact the far edge of the elevon which runs along the trailing edge of the orbiter's right wing.

And as you are picking out detail in the dimness of the fully-enlarged image, perhaps stop and consider just how close all that surrounding iron is to the untouchably-delicate surfaces of the Space Shuttle. Just how close they have managed to roll the unyielding steel mass of a multi-million pound high-rise hotel to a thing that can never be touched.

Yes, the Space Shuttle was a Wonder of the World. But the Great Rotating Service Structures at Launch Complex 39 were also, and equally, Wonders of The World, too.

And the Great Crazed Mechanisms of the finished pad, a second copy of which we were at that time involved in constructing, just down the road from here, surround it all in mute testimony as to what can be done, when people set themselves properly to a task.

Return to 16streets.comACRONYMS LOOK-UP PAGEMaybe try to email me? |